Highland farmers in Maguindanao endure conflict, food insecurity and El Niño

Strong El Niño in progress and to persist into the second quarter of 2016

The Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) on 30 September announced that a mature and “strong” El Niño now prevails in the tropical Pacific Ocean, upgrading the categorization from “moderate” conditions observed in the four months since June. PAGASA projects that the current El Niño event may intensify to a strength comparable to or even surpassing that of the 1997-1998 El Niño, which was among the strongest on record to date, and is likely to persist until the second quarter of 2016. Forecast models suggest that large parts of the country would be affected by below-normal rainfall and above-normal temperature until May or June 2016, before the weather system transitions into the rainy season.

Dry spell and drought conditions are feared to impact the country’s agricultural and energy sectors as well as food security. Prolonged drought can drastically cut down the production of local crops such as rice and corn, as well as fisheries yield. The 1997-1998 El Niño affected 74,000 hectares of agricultural land in 18 provinces of the Philippines. The strongest impact was felt in Mindanao, where almost half a million agricultural families faced severe food insecurity. The current El Niño episode has already affected over 32,000 hectares of rice fields which are left idle due to dry conditions in the first three quarters of the year.

Highland farmers in Maguindanao particularly vulnerable

Ernesto Sangcopan, an indigenous T’duray farmer in central Mindanao, is worried that the intensifying El Niño might bring more dry weather in the coming months, cutting agricultural yield in the already resource-exhausted community. Ernesto lives in Sitio Ba-ay, a hilltop village of about 110 T’duray families in the municipality of Datu Saudi Ampatuan, Maguindanao province. The community settled there some 15 years ago after fleeing conflict in its ancestral land on Firis Hill located 13 km away. As Sitio Ba-ay is located near a military check point, frequent harassment by opposing armed forces continues to this day.

The main source of livelihood in Sitio Ba-ay is corn, mung beans, peanuts and root crops farming. With good weather, Ernesto’s farm can be harvested twice a year, yielding 15 to 18 sacks of corn or PhP10,000-15,000 (US$210-320) per harvest. Between November 2014 and April 2015, the community missed a whole planting season due to the lack of rain. Ernesto resorted to selling firewood and charcoal but the sales hardly cover the expenses of horses and rented motorcycles to carry the produce and woods over rough terrain to reach the main road.

Maguindanao is likely to experience a dry spell from October to November and drought from December to January 2016, according to PAGASA. Small-scale farmers in highland communities like Sitio Ba-ay are considered particularly vulnerable to the drying effects of El Niño due to limited water resource and coping mechanisms. Lowland communities on the other hand have alternative livelihood options such as converting dried but fertile marshland to grow cash crops that are resistant to drought.

Maguindanao, along with 15 other provinces in Mindanao, was found moderately food insecure by the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification chronic analysis conducted by FAO and partners in January. WFP in the preliminary results of its combined food security assessment cited that the province was 29 per cent moderately food insecure and 2 per cent severely food insecure.

Local and national authorities step up mitigation measures

To mitigate the adverse effects of El Niño, local authorities are pre-positioning relief items for indigenous communities in eight municipalities of Maguindanao province including Datu Saudi Ampatuan. National government-implemented measures include: provision of improved water systems and drought-tolerant crop varieties for farmers, cloud-seeding operations to induce rain in major watersheds and drought-affected communities, water rationing and public campaigns on water conservation. International organizations are monitoring the situation closely to augment the government response as necessary.

Despite persisting insecurity and other hardships, Ernesto is determined to stay in Sitio Ba-ay, because “there’s nowhere else for us to go”. Timely and well-targeted assistance to mitigate further effects of conflict and El Niño is essential to support the already-vulnerable communities like Sitio Ba-ay to cope with difficulties and allow for indigenous people like Ernesto to maintain a little peace in what they now call home.Small-scale highland farmers in Mindanao are found particularly vulnerable to the drying effects of El Niño due to limited water resources and livelihood alternatives.

Two years later: Zamboanga IDP portraits

It is still a long way to normalcy, as far as the 5,700 displaced families are concerned. Over 24,000 families or about 118,000 people were displaced as a result of the Zamboanga siege in September 2013, when the government forces and a faction of the Moro National Liberation Front clashed in the city centre. Two years later, some 28,500 internally displaced people (IDPs) are left with no permanent homes. Two thirds – some 17,200 people – are staying in 12 transitional sites across the city, while an estimated 11,300 others are “home-based” IDPs who are either hosted by relatives and friends or availing of the government’s house rental assistance.

“Our identification card is gold”

“Our identification card is very precious to us. It is like gold - if we lose this, we lose everything,” says Jomar Sapii, a fisherman from Sumariki Island. Jomar is one of over 400 villagers of Sumariki displaced by the September 2013 siege. He is now staying with relatives at the mainland barangay (the smallest administrative unit in the Philippines) of Talon-talon.

Shaina Gani, a displaced mother of four, explains that the cards serve as an entry pass for her husband and his fellow fishermen of Sumariki Island who frequent their village to fish. “Without the ID, our husbands cannot get through the island to fish. Fishing is the only way we support our children,” Shaina said.

It took over a year for the city authorities to allow displaced families of Sumariki to set foot in their place of origin. The permit to return, however, is still conditioned and is temporary. According to Senior Superintendent Angelito Casimiro, the Zamboanga City Police Director and one of the three signatories to the identification cards, the cards are “imposed by the local government unit as part of the monitoring system of the Zamboanga City Roadmap to Recovery and Reconstruction (Z3R).” The identification cards are to be surrendered when IDPs are transferred to permanent housing.

Laundry for school fare

Apoh Arnado and her two grandchildren are staying in Mampang-1 transitional site, the largest IDP site in the city with some 4,600 people. She adopted two of her many grandchildren, Nuraisa in the 8th grade and Farhanna in the 7th grade, “because they don’t have parents anymore.”

The family used to live in Rio Hondo, one of the neighbourhoods worst affected by the September 2013 conflict, where she put up a small retail store. “I was strong for my age then. I could go to the market to buy things for my store or my grandchildren could. It was hard but we managed because of the proximity of our house to the town centre”.

But the conflict forced them to flee home, first to an evacuation centre in an open sports complex and then to Mampang. Dire living conditions at the evacuation centre took a toll on Apoh’s health. “You see I am very old, the heat, the congestion and the lack of medicine made me weak.”

While the housing unit in Mampang-1 is spacious enough for Apoh and her grandchildren, now she has to struggle to support the family. “I can hardly walk now, and we’ve lost our little savings from my store. This place is very far from the city centre where I can buy goods to sell. So now I walk around begging neighbours to let me wash their clothes for a fee. I need to raise money so I can send my grandchildren to school,” she shared.

City authorities struggle to provide durable solutions to displacement

The national government has allocated PhP3.5 billion ($75 million) for the Z3R aimed at providing recovery and rehabilitation assistance to the families displaced by the September 2013 conflict. In addition, the city received donations amounting to PhP22 million ($470,000) and PhP50 million ($1.1 million) from the national Department of Social Welfare and Development as transitory expenses.

The city authorities, however, are struggling to coordinate early recovery assistance for the displaced families and their access to water, light, livelihood and sanitation facilities remain irregular or insufficient in many IDP sites including Mampang, Lupa-Lupa and Mariki. While the government has assured that the majority of the remaining IDPs would be provided with newly constructed permanent homes by the end of 2015, most of these permanent housing units are being built without sustainable utility services.“Without the ID, our husbands cannot get through the island to fish. Fishing is the only way we support our children.”

- Shaina Gani, home-based IDP and a mother of four

Violence displaces Lumads in Surigao del Sur

About 4,200 people flee homes following killings of community leaders

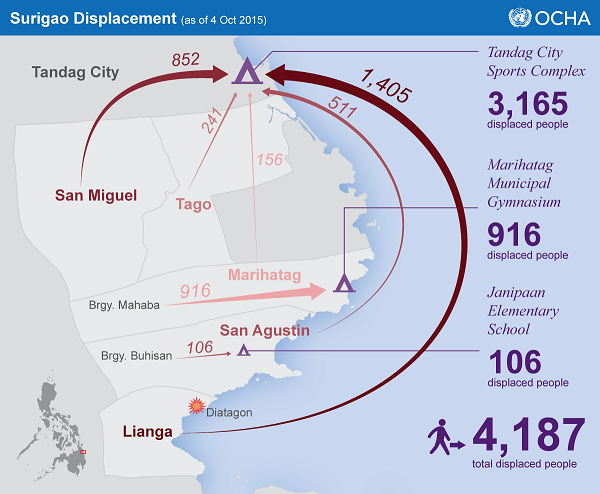

Hundreds of families, mostly from the indigenous Lumad communities, fled their homes following the alleged attack by a paramilitary group against a community-run school in Lianga municipality of Surigao del Sur province in northeastern Mindanao on 1 September. The school director and two community leaders were killed in the attack. As of 4 October, over 800 families or about 4,200 people remain displaced from five municipalities of Lianga, San Agustin, Tago, San Miguel and Marihatag, according to the Regional Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Office of Caraga. The majority of the IDPs are staying in a sports centre in the provincial capital in Tandag City.

The authorities at the sub-national levels provided food packs, non-food items, water, sanitation, hygiene and medical support. With the pre-positioned relief items running low on stock, the province on 19 September declared a state of calamity, which enabled access to the government’s quick response fund to continue providing assistance to the IDPs. Local civil society and private sector partners also distributed relief items and conducted psychosocial consultations for displaced children. UN agencies and ICRC are coordinating with the local authorities to extend support as needed.

The UN Special Rapporteurs on the rights of indigenous peoples, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, and on the situation of human rights defenders, Michel Forst, called on the Philippines Government to launch a full and independent investigation into the killings of three “human rights defenders” in a statement released on 22 September.

A month after the killings of indigenous community representatives, about 4,200 people remain displaced from five municipalities in Surigao del Sur province, northeastern Mindanao.

In brief

Gender checklist for disaster risk reduction

The Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) Gender Checklist is a tool to ensure that all programmes and activities of public institutions for disaster risk reduction are gender inclusive and responsive. A core team of gender experts from the Official Development Agencies-Gender and Development Network, consisting of foreign donor agencies, key government agencies on gender including the Philippine Commission on Women and the National Economic and Development Authority, UN Agencies and INGOs, drafted and validated this tool. The checklist will be presented to the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council for adoption in October. The checklist is envisioned as the DRR component of the Philippine Harmonized Gender Guidelines, which consolidates gender checklists for different sectors, including agriculture and tourism, to help stakeholders to collectively address gender issues and challenges.