Displacement – a way of life in Maguindanao

31,500 people remain displaced by clashes in Maguindanao

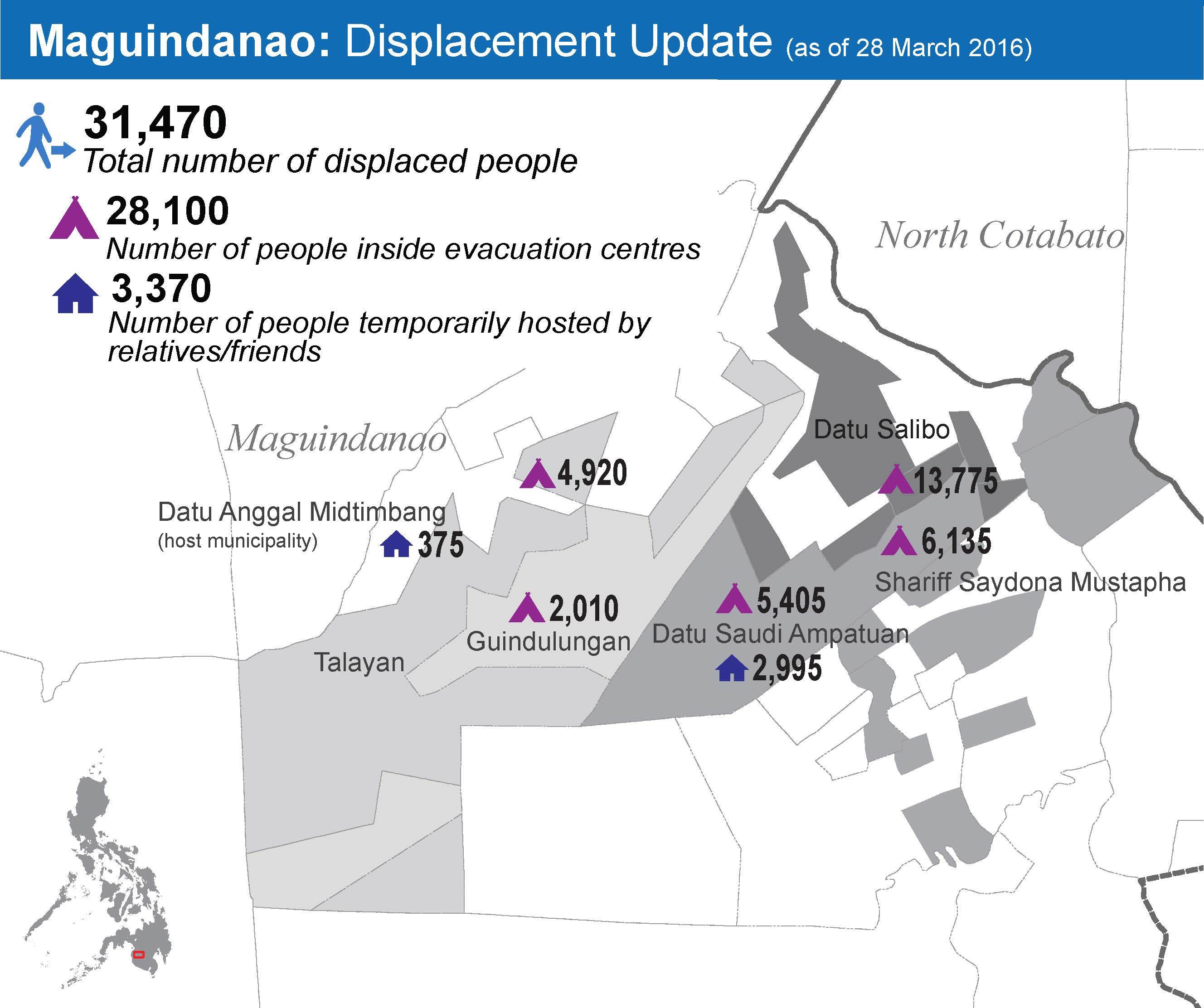

Continuous clashes between Government forces and armed groups since 5 February displaced over 41,800 people in six municipalities of Maguindanao province. While some have returned to their homes, about 31,500 people remain displaced as of 28 March, according to the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). The majority of the internally displaced people (IDPs) – about 28,100 – are staying at 13 evacuation centres, while the remaining 3,400 people are “home-based” IDPs hosted by the neighboring communities

Many of the displaced families and their hosts are the same people affected by the Government’s military operations against the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF) – a break way of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front seeking independence for Bangsamoro – in early 2015, which displaced over 148,000 people in Maguindanao province.

Host communities burdened by frequent and long-term displacement

Recurrent displacement has become a way of life for most communities in Maguindanao and the adjacent provinces of central Mindanao. A large number of people displaced by recent conflict (some dating back to over a year) involving the military, the BIFF and other Moro groups have moved to urban centres to seek protection and support from their relatives and friends and larger host communities. Besides disrupting family life and livelihoods of the IDPs themselves, frequent and often long-term displacement has eroded the coping capacity of their already-poor host communities. They continue to share often-inadequate food and water as well as crowded shelter, sanitation and education facilities. Meanwhile, insecurity is constraining farmers from cultivating land, straining food security of the displaced and host households alike.

Erosion of the coping capacity of these displaced people and the impact this has on their hosts pose a challenge to local authorities and aid agencies trying to address the humanitarian situation in central Mindanao. Government assistance to displaced people has been limited to small food rations (e.g. two to three kilograms of rice and three tins of sardines per family to consume for several weeks), with an aim to prevent the relief goods from being accessed by armed groups. However, frequent violence has hampered regular access of the Government and aid agencies to the affected communities, making it difficult for the IDPs to meet their daily food needs without support from their host communities. Ironically, these host communities who are often the first responders to displacement are largely left out from organised humanitarian assistance, and this has created tensions and sometimes conflict between them and the IDPs.

Long term assistance to vulnerable communities key to lasting peace in Maguindanao

IDPs from areas where the BIFF is operational, mainly in the municipalities of Datu Salibo and Datu Piang close to Ligwasan Marsh, are suspected of supporting the BIFF. Restrictions on humanitarian access and limited relief efforts to these IDPs and their host communities may further alienate and frustrate them. This is feared to radicalise the communities and especially the youth amid political uncertainties following the recent setback in the peace process due to the delayed passage of the draft Bangsamoro Basic Law. Meanwhile, the BIFF may be gaining support from these communities as they become more vulnerable with fewer options. To prevent escalation of inter-group tensions and further suffering of the communities caught in the middle of recurrent fighting, there is an urgent need to strategically reach out to them with sustained humanitarian and development assistance.

Host communities of “homed-based IDPs” are often the first responders to recurrent conflict-induced displacement in central Mindanao, though their burden is largely overlooked in humanitarian assistance

Emergency health assistance following Typhoon Koppu

Typhoon Koppu and Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF)

“We evacuated before the typhoon to a local evacuation centre, but when I went back to my field after the storm it was all flooded and crops were damaged” said Sari Evangelista, a 46-year-old mother of five children at the crowded barangay (the smallest administrative unit in the Philippines) health station in Santa Juliana, Capas municipality of Tarlac province. On 16 March, she walked for four hours with her 11-month-old baby and 2-year-old son to the health station to receive their malnutrition screening and treatment.

Large areas of central Luzon including Tarlac were inundated for weeks due to heavy rains from Category-3 Typhoon Koppu (known locally as Lando), which traversed central and northern Luzon in October 2015. It was the most destructive typhoon of the year, which displaced over 1 million people at the height of the disaster, damaged some 137,700 houses and caused over US$200 million damage to agriculture.

In the wake of the typhoon, international aid agencies supported the Government with conduct of multi-sectoral rapid damage assessment and needs analysis and targeted provision of food, emergency shelter, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), health, camp management and camp coordination, agriculture, logistics, information management and overall coordination assistance.

To mitigate deteriorating food insecurity and address rising risks of malnutrition and diseases among the affected communities, the UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) allocated $1.5 million in November 2015 to support agricultural and health assistance in Nueva Ecija, Pampanga and Tarlac provinces in Region III and Pangasinan province in Region I. The CERF-funded projects of FAO and WHO are helping some 212,000 people affected by Typhoon Koppu, including 65,000 people from small-scale, rice-farming households whose crops were devastated in Region III. The projects include provision of certified rice seeds and fertilizers and essential health care and disease surveillance for a five-month period until April 2016.Emergency health project targets the most vulnerable among the typhoon-affected people

WHO as the co-lead of the country’s Health Cluster, in partnership with the health authorities at the national and local levels, ACF and IMC, has set up primary medical and surgical services and barangay-level disease surveillance and early warning systems across 18 selected municipalities in the four affected provinces. The project also screens and treats acute malnutrition cases of children under age five in selected municipalities in Tarlac and Nueva Ecija provinces. Identification of barangays and municipalities targeted by the project took into account direct impact of Typhoon Koppu (density of damage to houses and farms) as well as health system vulnerability (pre-existed health services per population), poverty index, history of infectious diseases and pre-typhoon malnutrition incidence in the affected communities.

Barangay Santa Juliana recorded the highest malnutrition rates among children under age five in Tarlac province even before the typhoon. At the barangay health station, bi-weekly doctor visits are complemented by local healthcare workers providing acute malnutrition screening and supplemental feeding, immunisation and community health consultations. Most patients in this barangay are indigenous Aeta people, like Sari, who live a nomadic life in isolated mountainous communities of Luzon. Many of them had to walk long distances with young children to reach the nearest local health facilities.

At the beginning of the response, dengue was considered a prominent risk to the typhoon-affected population. Dengue cases in Luzon were already on the rise since earlier in 2015, and prolonged flooding due to the typhoon was feared to accelerate breeding of mosquitos that transmit the disease. While dengue cases after the typhoon increased in some of the affected communities, continuous surveillance and monitoring showed no outbreaks of dengue or other infectious diseases.

In addition to IMC providing regular medical visits to different local health facilities, where over 50 people are treated daily, ACF has deployed mobile health teams to conduct nutrition screening in hard-to-reach areas of the mountainous communities of central Luzon. The project has helped to extend health services and disease surveillance to those who cannot walk far (including the elderly) and also to adapt the programme to the nomadic nature of Aeta people.Addressing residual health needs in post-typhoon recovery and beyond

While CERF is effective in addressing acute health needs of those worst hit by Typhoon Koppu, emergency assistance alone cannot sustain adequate health services in these communities. Healthcare professionals of Koppu-affected communities are concerned about what would happen to their patients after May when the typhoon response programmes are completed. For Sari, only three out of her five children have undergone nutrition screening so far. Many other mothers are worried if they could receive essential immunisation and nutrition treatment for their children before the current assistance ends.

As part of efforts to mainstream emergency response into regular health programming, WHO is working closely with the Department of Health and UNICEF to facilitate implementation of Community-based Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) schemes in the Philippines. The initiative aims to integrate into the national health strategy funds and resources necessary to achieve long-term health in the vulnerable and remote communities beyond humanitarian response.UN agencies and partners with support from the UN emergency fund provide life-saving food security and health assistance following Typhoon Koppu in central Luzon.

CERF-funded Emergency health project reaches the most vulnerable among the affected, including indigenous Aeta people.

Community-based management of acute malnutrition key to achieving sustainable health in the typhoon-affected communities.

Cash as an evolving modality of emergency assistance in the Philippines

Cash-transfer programming (CTP) is not a new modality of assistance to disaster-affected people in the Philippines. Cash was used in the responses to past major emergencies including Typhoons Ketsana and Parma (2009), flooding in central Mindanao (2011), Typhoon Washi (2011) and Typhoon Bopha (2012).

However, it was not until Super Typhoon Haiyan (known locally as Yolanda) devastated the central Philippines – killing 6,300 people and displacing over 4 million- that CTP was scaled up by both national and international actors. During this response, at least 45 international aid agencies implemented CTP to address critical needs of 1.4 million people for shelter, food and livelihoods. UN agencies, Red Cross and NGOs partnered with the Philippine government and local financial service providers with long-standing practice of processing the national social protection programme and remittances of Filipinos. Inter-agency Cash Working Groups (CWG) were set up in Manila, Guiuan and Roxas to serve as the platform for both strategic and technical coordination of CTP.

As aid agencies expanded direct cash distributions and various cash-for-work schemes, concerns were raised over possible aid duplication and need for standard-setting on how and in which sectors CTP should be used. The Manila-based CWG has continually convened to address these challenges from the height of the typhoon response into the successive phases of recovery and preparedness for new disasters, capturing key lessons in CTP implementation.

The Canadian Embassy on 3 March presented its review of Canada-funded NGO projects for humanitarian and early recovery assistance mostly in Leyte and Eastern Samar provinces following Typhoon Haiyan. Eleven out of 15 NGOs which received a total funding of C$15.9 million ($11.9 million) reviewed their projects on shelter, livelihood, WASH and (re)construction of schools and daycare centres. The review cited targeted provision of time-bound unconditional cash transfers to vulnerable households, strategic provision of conditional cash transfers coupled with technical assistance to existing cooperatives and associations with trusted track records, and close coordination with the national and local authorities in CTP implementation aimed at strengthening links between actors in value chains as good practices.

The CWG, with its now over 50 member organisations including UN agencies, NGOs, financial service providers and government agencies, meets monthly through its 11-bodied Steering Committee and quarterly in a larger General Assembly. The group’s latest activities include development of a template for new partnership agreements to quickly scale up CTP at the onset of large-scale disasters and enhanced targeting of CTP beneficiaries based on sex- and age-disaggregated and other vulnerability data.Cash Learning Partnership, a key member of the CWG, on 13 February launched the 100 Days of Cash campaign inviting various stakeholders engaged in CTP to jointly develop an Agenda for Cash ahead of the World Humanitarian Summit. The campaign aims to bring together voices and experiences of CTP practitioners and beneficiaries from the Philippines and elsewhere to establish a “framework of action, change and mutual accountability” for cash-based programming as effective means of humanitarian assistance.

Strategic use of conditional and unconditional cash transfers delivered in close coordination among local, national and international stakeholders can drive effective humanitarian response.