Philippines: civil-military coordination in humanitarian response

The Philippines, by virtue of its location, is prone to natural disasters. With the trend of increasingly severe and destructive weather disturbances unlikely to change, more communities are likely to be exposed to hazards.

The country has thus developed a comprehensive disaster management system utilized down to the local level to ensure preparedness, effective response and prompt recovery. When a disaster overwhelms national capacity, however, the Philippines may request international assistance, including military assets, to support the national response.

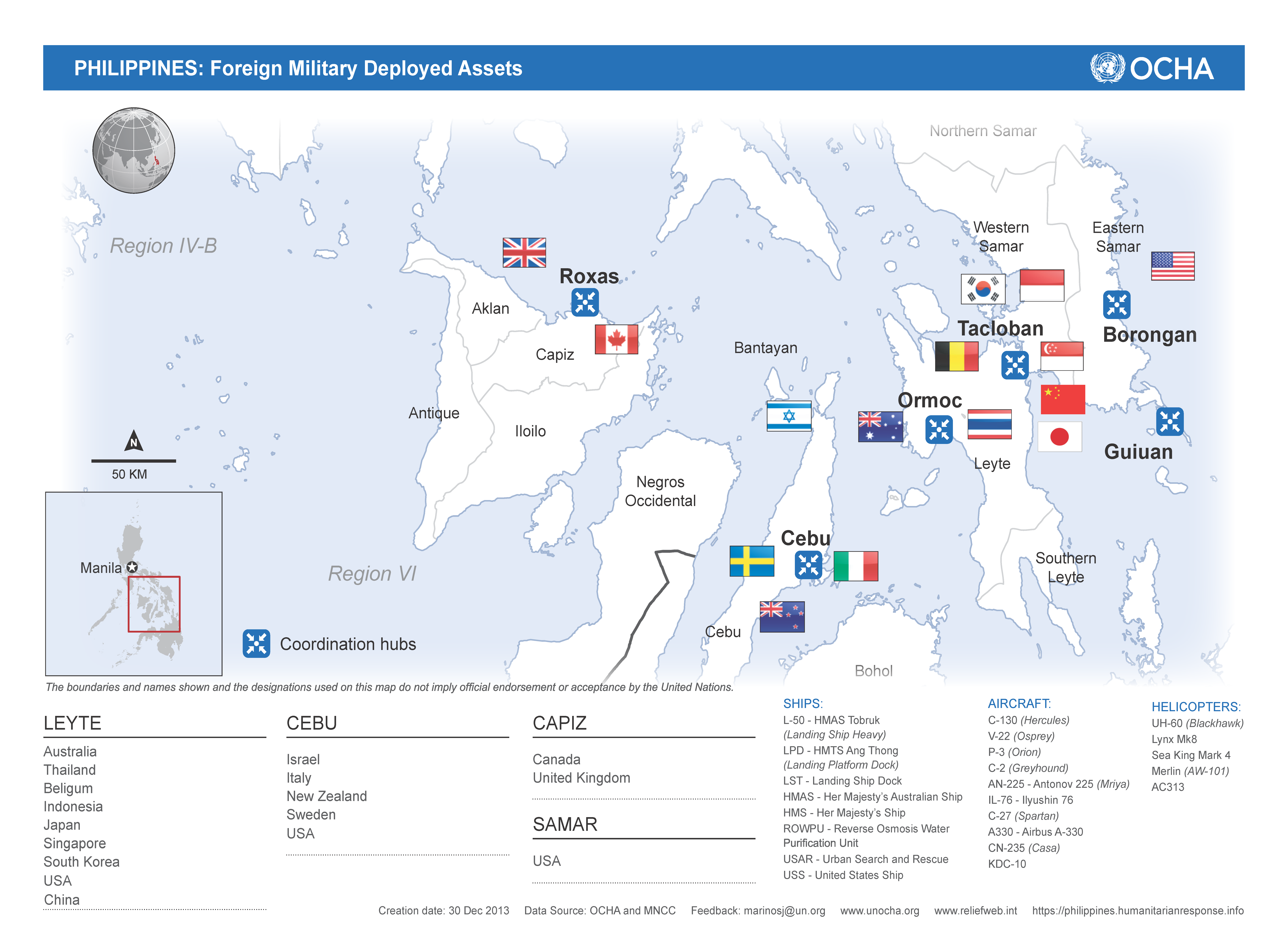

After Typhoon Haiyan (known locally as Yolanda) in 2013, military assets consisting of air, naval, medical, engineering and communications capacities, as well as personnel were deployed from 21 Member States. Thousands of foreign military personnel worked closely with the humanitarian community at the height of the relief operation. With overlapping capabilities and specific missions coupled with cultural differences, the arrival of foreign militaries posed coordination challenges with civilian humanitarian actors.

The military’s role in humanitarian response

In the Asia-Pacific region, military resources are often part of the first response after natural disasters and make a valuable contribution. The prominent engagement of the military in humanitarian operations is a by-product of its unique structure, discipline, training, manpower, equipment and the determination to bolster resilience amidst the chaos.

Coordination among the different actors is critical for sharing information, planning and dividing tasks. This is where the United Nations’ Humanitarian Civil-Military Coordination framework helps facilitate interaction between civilian and military actors, which is essential to protect humanitarian principles, avoid competition, minimize inconsistency and pursue common goals.

In the event of a disaster, the Government and affected communities rely on the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) to be among the first to respond. The AFP has as one of its critical mission areas Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Response (HADR), and it leads the Search, Rescue and Retrieval Cluster of the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC). It also provides manpower and logistics and communications support to other government cluster agencies.

Institutionalizing the CMCoord framework

In 2014, an After-Action Review (AAR) looked at the effectiveness of coordination among humanitarian organizations, the military and police, and how foreign military assets were tasked to support national and local authorities during the Haiyan response. The AAR resulted in a recommendation to build capacity through training and institutionalizing humanitarian civil-military coordination.

With this in mind, OCHA and the Office of Civil Defense (OCD) are conducting a series of CMCoord trainings for the NDRRMC agencies to help build an understanding of the cluster system and how humanitarian civil-military coordination fits into existing disaster response arrangements with or without the involvement of international actors.

Ola Almgren, Resident Coordinator and Humanitarian Coordinator, says these efforts are, “aimed at developing trainers and practitioners from the military and government who can be deployed within the country and coordinate civil-military activities when needed.”

Over 300 members of the military, police, other Government agencies and the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) have been trained so far. OCHA Philippines partners with AFP and OCD to conduct the pilot training for military field commanders under the AFP Unified Commands. These are the units mandated to conduct immediate HADR operations in their areas of responsibility and to support other affected areas as needed. Similar training was conducted in June 2016 for senior officers of the General Headquarters and Army, Navy and Air Force branches.

Addressing the officers attending the recent training workshop, Almgren assured that, “OCHA Philippines will continue to support the Government to ensure it is always at the forefront of disaster response.”Regional Consultative Group on CMCoord

The Philippines, represented by OCD Administrator Undersecretary Alexander Pama, was elected in 2015 as the first chair of the Regional Consultative Group (RCG) on Humanitarian Civil-Military Coordination. The RCG will facilitate the coordination of operational planning between civilian and military entities preparing to respond to major disasters in the Asia-Pacific.

“The Philippines is honoured to be the first chair of the RCG,” says Pama, “and we wish to share our experiences on disaster management, particularly in receiving international humanitarian assistance and foreign military assets.”

As chair, Pama monitors the work plans of countries highly vulnerable to large-scale natural disasters like Bangladesh, Indonesia, Nepal and the Philippines. The chair also advocates streamlining civil-military coordination exercises and including civil society organizations and the private sector.

For its own work plan, the Philippines will integrate the CMCoord concept into existing disaster preparedness policy and guidelines. It also wants to leverage the Philippines International Humanitarian Assistance Cluster of the NDRRMC to strengthen coordination and improve situational awareness. “We have a wealth of lessons learned and good practices which the international community can draw upon to help improve disaster risk reduction policies,” Pama said.

The Philippines is also part of an advisory group developing common humanitarian CMCoord standards to enhance the predictability, effectiveness, efficiency, and coherence of employing military assets, and maintain a distinction in the roles and responsibilities between the humanitarian and military responders.Over 300 individuals from the military, police, Humanitarian Country Team and other government agencies have been trained so far in the UN’s CMCoord concepts, principles and practical approaches.

“The Philippines is honoured to be the first chair of the RCG, and we wish to share our experiences on disaster management, particularly in receiving international humanitarian assistance and foreign military assets.”

- Alexander Pama, OCD Administrator

Rapid humanitarian response in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao

The Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), comprising the provinces of Maguidanao, Lanao del Sur, Basilan, Sulu and Tawi-Tawi, has long experienced sporadic armed conflict that causes displacement and suffering of already impoverished people in the region. AFP frequently engages in law enforcement operations against militant groups like the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters in Maguidanao, the Maute group in Lanao del Sur and the Abu Sayyaf in Basilan and Sulu. Long-standing feuds between armed groups and families, known locally as rido, have also caused repeated displacements in central Mindanao.

Added to this, recurring natural hazards, such as flooding along marshlands, watersheds and low-lying areas also affect communities on yearly basis. This past year, the ARMM provinces were among the worst affected by drought caused by El Niño. These frequent and recurring events have drained the meagre calamity funds of local governments, degrading their capacity to respond to further disasters this year.

In 2013, ARMM established the Humanitarian Emergency Action and Response Team (ARMM-HEART) to augment the humanitarian assistance of local governments in the region to people affected by armed conflicts and natural disasters. ARMM-HEART works in partnership with the Regional Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council. It created an operation centre that brings together regional offices of the national government and aid agencies to carry out rapid assessments and provide basic relief items. The Cotabato-based operation centre also coordinates the work of the Regional Human Rights Commission, the Philippine National Police, AFP, OCD and other stakeholders in partnership with the local authorities to respond rapidly to save lives.

Ramil Masukat, the director of ARMM-HEART, says, “We conduct training on basic rescue and other things that build the capacities of the barangay officers and municipal disaster risk reduction and management officers.”

ARMM-HEART also has its challenges in responding to conflict and natural disasters. Coordination among the different levels of local government with the ARMM government remains an issue. In Marawi City in Lanao del Sur, the organization is working to strengthen the coordination between the provincial and municipal authorities and other stakeholders to respond better to those affected by the conflict in the municipality of Butig.

“There are many challenges,” Masukat said, “but most of the time we face the limited resources of the local governments, so sometimes ARMM-HEART acts to cover most of the relief assistance to the [affected people] during disaster operations.”

Security is another concern. “It is always a challenge to respond quickly due to security concerns of the staff,” he said.

This year, ARMM is implementing a Humanitarian and Development Action Plan (HDAP) with funding from the national government to address the mid- to long-term needs of people affected by conflict and natural disasters. It involves constructing roads and bridges, providing farm animals and equipment, training women and out-of-school youth, building the capacity of local volunteers and rehabilitating health facilities. HDAP is expected to improve not only the immediate response to disasters but provide livelihood support to enable communities to recover from repeated shocks.

“There are many challenges, but most of the time we face the limited resources of the local government units, so sometimes ARMM-HEART acts to cover most of the relief assistance to the [affected people] during disaster operations.”

- Ramil Masukat, ARMM-HEART Director

The Philippines’ unique history of embracing refugees

On 20 June, we recognized the 16th annual World Refugee Day. The UN Refugee Agency marked the event by launching its #WithRefugees petition to tell governments they must work together and do their share for refugees.

Since the early 20th century, the Philippines has welcomed multitudes of refugees from around the world when other nations would not, and has actively engaged to resettle them. UNHCR Representative in the Philippines, Bernard Kerblat, extensively researched the history of asylum seekers in the Philippines, grouping them into nine waves.

Welcoming refugees from abroad

The first group to seek refuge in the Philippines arrived in 1923 as part of a larger diaspora of “White Russians” escaping the Communist Red Army. Most of the 800 exiles were subsequently transferred to the United States (US), but some chose to remain.

Conflicts resulting from the spread of fascism, communism and imperialism across Europe and Asia that would peak as World War II spawned the next six waves of refugees. The second wave came between 1934 and 1941, when over 1,200 European Jews were settled in the country. The Government, determined to do its share, planned to resettle up to 10,000 Jewish refugees in Mindanao, but the plan never materialized.

At the same time, the third wave comprising thousands of Spanish Republicans fleeing civil war arrived. By 1940, the fourth wave of refugees, this time from China and the British colony of Hong Kong was well on its way. That year the Philippine Immigration Act of 1940 was enacted limiting the annual number of immigrants to 500 of any one nationality. It included, however, a provision allowing the president “to admit aliens who are refugees for religious, political or racial reasons.”

The latter half of the 20th century would see significant increases in the number of refugees seeking asylum in the Philippines. The fifth wave of more than 6,000 White Russians arrived between 1949 and 1951 and settled near Guiuan, Eastern Samar, making it one of the largest refugee camps in Philippine history. The conflicts in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos brought successive waves of refugees. From 1975 to 1992 about 400,000 Indochinese refugees passed through processing centres in Palawan and Bataan. A thriving community of nearly 3,000 Vietnamese remains in Palawan.

In between, the 1979 Iranian Revolution led several thousand Iranians studying in the Philippines to seek refugee status due to the regime change in their country. By the early 1990s, Iranians formed the majority of non-Indochinese refugees in the country.

Finally, the ninth wave saw some 600 people from East Timor flee to the Philippines in 2000 to escape the violence of its war of independence from Indonesia. The refugees were repatriated after security was restored. Most recently, the Government said it is open to sheltering Rohingya refugees from Myanmar.

The Philippines’ commitment to protect the rights of all refugees

In spite of the Philippines’ rich history welcoming refugees, it struggles with the recurrent displacement of its own people by conflict and natural disasters. In 2015, UNHCR recorded over 400,000 people in Mindanao forced to flee, with one in ten of those repeatedly displaced, mostly by conflict, rido or generalized violence. It has yet to pass a law on the rights of its own populations displaced internally by conflict and natural disasters. A 2013 bill was vetoed by the president, and a 2015 iteration was never voted on and will need to be re-filed when the new Congress convenes in July.

At the World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul, Turkey, in May, Department of Social Welfare and Development Secretary Corazon Soliman announced the Philippines’ commitments to the five Core Responsibilities of the UN’s Agenda for Humanity, including “to uphold international laws and norms on human rights, armed conflict and refugees” and to work on the passage of the IDP bill.

The Philippines is a signatory to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1954 Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons.Since the early 20th century, the Philippines has welcomed thousands of refugees from around the world when other nations would not, and has actively engaged in efforts to resettle them.

In brief

HCT joins National Earthquake Drill

HCT was invited for the first time to participate in the quarterly National Simultaneous Earthquake Drill, which took place on 22 June at Camp Aguinaldo in Quezon City, which simulated a 7.2 magnitude earthquake striking metro Manila—a catastrophic event that would likely require an international humanitarian response. NDRRMC and HCT exercised their processes for requesting and coordinating international resources.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

NDRRMC and HCT jointly exercised their processes for requesting and coordinating international resources.